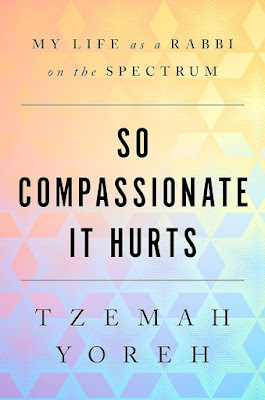

Tzemah Yoreh, So Compassionate It Hurts: My Life as a Rabbi on the Spectrum. N.p.,

Modern Scriptures, 2022.

“Nothing about us, without us”

These words have long been the disability community’s mantra. But even now it is routine for anyone living with visible conditions to have “experts” tell “us” what we need. So it is hardly a surprise that neurodiversity, being less visible, is one where it is still routine to brush aside the thoughts of those who live with it. “We” are categorized, labeled, given diagnoses of what is “wrong” and needs to be “fixed.” We are rarely asked what would really help, and even more rarely is there any acknowledgment that we have strengths and abilities.

Rabbi Yoreh’s story

begins with a story of self-discovery that is frequent for many of today's adults: knowing

they are different, but not having good descriptive terminology, all the time

seeking to understand differences. In the process of exploration, he upends the medical model of a deficit

to be fixed and brings us to a social model of having much to contribute. The book is his invitation to join a quest to learn if

his success is “because of” or “in spite of” the gifts which autism brings (35).

Central to discovery is the charge to love your neighbor as yourself (Leviticus 19). To the author's mind, surface answers are not sufficient. He finds resolution by realizing that the task is impossible, rather is it one to strive for. He finds strength from living in a world that has not been built for people like him, which has

resulted in better realization of the obstacles that others face.

From that realization he finds other characteristics: a sense of fairness and equality coupled with an understanding that while needed, authority is often balanced toward those with various advantages. He is not a good liar, which is a “freeing” gift (40). But while freeing, this gift has another side: a heightened sense of conflict and of cognitive dissonance. In the end, it creates compassion for those whose sense of equality leads to understanding and kindness in creating space for those who are different.

Another step is the perception that neurodiverse people wish to be left alone, and thus, we hear again, that they lack compassion. The inside reality, however, is that social interaction is draining due to the need to figure out what others are really saying in a given situation. He gives an analogy to expending calories like an Olympic distance runner, but being unable to sweat, and as a result, his CPU overheats. One can love an activity but need breaks. This, in turn, leads to a need for patterns in life—with the result anything out of the pattern is a stress factor.

Finally, a theological note (and complaint about history education). Many studies link autism to atheism or agnosticism. This is, as I read it, not so much a lack of belief as an inability to grasp the idea of a great otherness, stemming from that pragmatic nature. The early church “fathers” include a school of apophatic theology—one that is very similar, but recognizes some kind of source to all, however inconceivable. Our systems don't do a good job of transmitting ancient wisdom, leaving us to continually re-invent the wheel!

In the end, whatever chasm lies between understanding the world of neurodivergence and neurotypicality (whatever that might be) and one's idea of the divine, I am sure that she is thrilled with the rabbi’s mantra of “being as kind as possible” (104). If more people had such a level of compassion (or listened to those who do), this world would be a far better place.

Disclosure of Material

Connection: I received this book free from the author and/or publisher through

the Speakeasy blogging book review network. I was not required to write a

positive review. The opinions I have expressed are my own. I am disclosing this

in accordance with the Federal Trade Commission’s 16 CFR, Part 255.

Rabbi On The Spectrum (Facebook) / Author's website