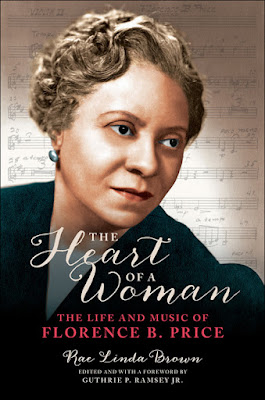

A review of Rae Linda Brown, The Heart of a Woman: the life and music of Florence B. Price (Guthrie Ramsey Jr, ed.) Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020. (NB: the author died in 2017; the editor updated some of the information for publication).

Music, the universal language! Yet how often is it clouded by assumptions, such as being divided into two worlds, one the product of grumpy old white Europeans, and the other dominated by young flash-in-the-pans who often trade pyrotechnics for talent? But like many others, this is a false dichotomy, and this book is an excellent example.

While listening to “Performance Today” one morning, I heard something unfamiliar but interesting--folksong settings by Florence

Price. They reminded me of Beethoven’s similar settings, along with Bach’s

appropriation of popular tunes in his works. Further commentary and a little

research gave more information, and when I learned about this biography, it was a

must-read.

Price,

born in 1887, died in 1953. Her life spanned the rise of legal discrimination,

some of the first tentative steps to end that system, and challenged a dual

glass ceiling in music—women and color in the formal settings of orchestral

music. And she reached into the realm of popular music with taste and style.

There are many parallels here to events found in

Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: the origins of our discontents. For example, Brown refers to an early Jim Crow law, the Tillman Separate

Coach Act of 1891 as “caste legislation” passed not out of sudden aversion, but

in rejection of the social and political advances of middle-class blacks (29). It was an event that influenced Price's life.

For a young musician such as Price, discrimination was

particularly acute, as most whites thought of themselves as cultured, while

Blacks were presumed to lack culture and refinement—as well as the ability to gain it. But all the same, and partially motivated by such Jim Crow laws, Price moved from Arkansas to attend the New England

Conservatory of Music in 1903. In her course of studies over three years, she

did well. But she still faced racial discrimination, especially in obtaining

housing.

At graduation, she returned to Little Rock. At that

time, she faced continuing efforts to disenfranchise Blacks, as well as unequal

pay. So she took a teaching position at Clark University, Atlanta. After a

short time, she returned to Little Rock and married a lawyer, Thomas Price, who

was active in legal challenges to discriminatory provisions. She also followed a typical path: she soon left full-time teaching to raise the couple’s children, but did continue

private lessons, which gave the opportunity to compose exercises for her

students.

In another Caste parallel, increasing racism through the 1920s, turning into outright terrorism from groups such as the KKK, prompted another departure. The family moved to Chicago in 1927. Chicago was seen as a promised land to many, especially musicians, being the center of jazz and the developing gospel movement. Here, Price continued to write songs, and also took up a pen name, “Vejay,” under which she wrote musicals and commercial jingles. But all was not well. Reflecting the experiences of many in the Depression, in 1931 she divorced her husband on grounds of abuse, and then remarried in six weeks.

But

there was breakthrough: in 1932, she completed her first symphony and won the

Wanamaker Foundation prize in that category, along with another for her piano sonata. Part

of the prize was that the symphony was played at the 1933 World's Fair by the

Chicago Symphony under Frederick Stock.

By

1934, she was separated. In 1935 she travelled to Little Rock to play a benefit

concert at Dunbar High School. In another parallel illustrating the events of Caste,

the school’s previous building had been condemned. The school board authorized

a new building but provided no funding. The Rosenwald Fund agreed to pay for a

building on the condition that it would be used for vocational training

only—leading to menial jobs, trapping its graduates in the caste system. The

new building opened in 1930, by which time the curriculum included the liberal

arts. In comparison, the (Central) Little Rock High School, built in 1927, had

much larger facilities but was restricted to whites only.

After

this, Price faded on the scene, apparently due to health problems. In the

middle of planning a trip to Europe that would include promoting her music she

died in Chicago on June 3, 1953. Much of her music was never published, and generally thought to be lost. But a 2009 discovery at at house in downstate St. Anne turned up more compositions, and some have also been found in Arkansas.

Price

appears to have been a woman of her times, but one who also sought to reach

beyond social limitations. Brown notes that she lacked the assurance and

aggression which are often associated with men, characteristics that are viewed

as necessary in professions to get ahead (often expressed as a man is

confident, a woman is bossy). As well, race compounded that. Although she did

well in Chicago, where the Chicago Defender referred to her as the dean

of composers, exposure to other areas did not happen in her lifetime.

While

that wider exposure did not happen during her lifetime, to some extent, the

ready availability of recordings has begun to change that. And, as I was

writing this, came news that the Philadelphia Orchestra has scheduled all of her symphonies for performance over the next seasons. These will be a welcome change for anyone interested in expanding their musical horizons.

Disclaimer:

I borrowed this book from the Indianapolis Public Library on the condition that

I would return it within three weeks. I kept that promise. I also have an undergraduate

minor in music, funded by a scholarship to Indiana University back in the days

when the state recognized and encouraged learning to think.