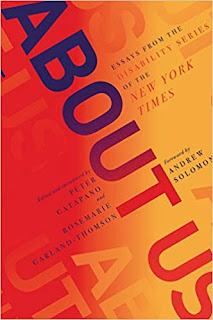

About Us: Essays from the Disability Series of the New York Times, Peter Catapano and Rosemarie Garland-Thompson, editors. New York: Liveright Publishing, 2019.

This book is diverse—as it ought to be, for disabilities are diverse—covering at least physical, neurological, intellectual, auditory, visual, congenital, acquired, and, to borrow a phrase from the (proper) translation of the ancient creed, “seen and unseen.” It collects 60 essays from a New York Times series of personal stories describing various aspects of living with a disability.

The collection begins with a foreword that discusses eugenics, the pseudoscience that began with Francis Galton, and which, after some preliminaries in the United States, led to Hitler’s atrocities. While eugenics has generally been disavowed around the world, pockets still remain, and more dangerously, an unseen residue still infects many policies and attitudes (including in the United States, where a Supreme Court ruling favoring it still stands).

Thus a valid claim that while disabled people lead “rich lives,” frequent limitations on work and other activities (which are not always valid, but socially constructed) lead to devaluation. One reason this happens is that one’s experience of living with a disability is very different from outside perceptions—again, “seen and unseen.” This is the reasoning of the familiar saying “nothing about us, without us” which is recalled in the title.

The diversity of the book makes a summary difficult. But there are several points which resonate with me and conversation partners. The first is the language that is used about conditions. There is less talk today of disability being a curse, tragedy, misfortune, or individual failure, but there is a lack of agreement on what terms to use. Perhaps as a more open body of history becomes part of our culture, and a wider, more diverse community flourishes, we will gain a better sense of cultural place and how to share.

Among the most stigmatized conditions noted in the book is mental illness. Much of what passes for discussion these days presents a monolith of danger. The truth is that both sanity and mental illness lie on a spectrum, and, most people spend some time at various points on that line.

Everyone is only an accident away from becoming disabled, and this proximity makes disability scary to most people. But rather than compassionate care, the response is often ableism. Ableism leads to categorization that devalues people. This is especially prevalent in the medical model of dealing with differences, where we become patients needing treatment rather than human beings with differences.

Thus ableism is an important factor in disability life, and has recently been receiving the attention it deserves. As with racism and sexism (among others), when disability is not considered in planning and design, ableism is at work. When it’s not considered, we end up with haphazard routes, difficult-to-find elevators, inaccessible planning, and other situations that are reminiscent of separate doors for blacks during the Jim Crow era. It’s all in a day’s life for those who live with the ultimate American irony—bootstrapping by refusing to give in to a body that one cannot control, and that medicine offers little help with. It also brings to mind the Nazi T4 program, which preyed on these factors. As my friend Kenny Fries, a scholar of the program states, it brings us to address the value of life, and reaches beyond abstract affirmations to the reality of ableism while ignoring social and design problems. .

This creates a world in which we must be resourceful and adaptable as we await and strive for a world of universal design. The example of OXO is noted here—the company began with hacks of kitchen tools to accommodate arthritis. Will that gain a chapter in history, or be overlooked yet again—or written off to some other origin?

The question of theology is always “where is God in this?” So while this is not a theology book as such, all of the above bears on theological concerns. And there are explicit theological questions and allusions. “People with disabilities are the unexpected made flesh” (53), just as the Gospels portray the irony of an unexpected messiah. There are also, as most of us would expect, references to faith healing and prayer for cures. A good question is raised in many of these accounts—who needs healing, the person with a disability or the attitudes of society? When one reads the healing stories in the Gospels carefully, it is not the disabled person’s faith, but that of the social group gathered around him that brings change. Neither is that change imposed. Bartimaeus was first asked what he wanted, and his answer was listened to – once again, “nothing about us without us.” Yes, there are also stories of messages from God delivered by those who are not involved. As I commented here, God is perfectly capable of sharing her plans with us, leaving us to wonder why it seems that this information is never shared with those who are most directly involved. Is that the ultimate ableism?