Recently, disabled

people and advocates have been speaking about another “ism” that diminishes

people—ableism. As I have joined with others in explaining, ableism makes false assumptions about disability and leads to

discrimination and exclusion. So I am pleased to join the Psalmist and be glad to enter this

house of the Lord and share some thoughts about reading a new book:

Kenny, Amy. My Body Is Not a Prayer Request: Disability Justice in the Church. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Brazos Press, a

division of Baker Publishing Group, [2022].

Gustav Mahler described

the final movement of his first symphony as the cry of a wounded heart. This book is a similar cry—more than once, Kenny states that she is

screaming. The stormy dissonance of the opening of the movement is reflected in

Kenny’s first page as she tells of an encounter: “God told me to pray for you .

. . . God wants to heal you.” Like Kenny, many of us have been there as the

ultimate ableism loads presumption upon presumption and tops it with a divine

imperative.

These early chapters are

hard, because the scream story continues with more recitations that will be

familiar to many people with disabilities. Like much racism, ableism lurks in structures beneath the

surface, formed on a foundation that we often overlook. Accommodations are

considered an add-on, a patch to the structure, not an essential of design.

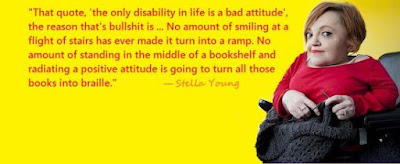

The implied statement of

ableism is that something must be fixed, that people with disabilities are not whole, and that our

faith is lacking. This leads the author to state that the real need is to be freed

from ableism. In the same process as outlined by Beth Allison Barr, where cultural notions create faulty theology, we see a chain of thought: disability makes people uncomfortable, leading far too many to presume

sin lies behind it, with the result that scripture is twisted to fit presumptions while overlooking the passages that don’t

fit those cultural notions.

Culture teaches us that

people are valued for their productivity, and disabled people are not

productive (and if they are, they require costly accommodations and extra

time). We are “ministered to” instead of “with,” reinforcing a segregated

second-class status, and silenced from instructing others. When the ADA was

adopted, some churches strongly opposed it, and many are still not compliant or

accessible (or when they are, clumsily so). It’s a sign that disabled people

are not considered fully human, which both picks up from and contributes to

eugenics.

What to do then? After

Mahler’s cry of wounded despair, hope emerges in themes of contemplation that

transform the despair. Kenny finds hope in disabled people who, among all

others, can best grasp that Jesus shows the way to transformation. His call to μετανοια has urgency. Although generally translated “repent,”

which has become a religious buzzword with no more meaning than empowerment or some of the other corporate gibberish that has infested our language, its call is to renew the mind, to

transform our ways. Instead of the medical model of fixing things, she asks us

to embrace disability and use that model in interpreting Scripture. In this light, the healing

narratives are not about cure and eradication, but restoration and

acceptance. Old stories gain new life: Jacob is changed from a schemer to a

forgiving Israel with a limp.

In these and many other

examples, we come to understand interdependence in a renewed and transformed society.

Accessibility becomes the beginning point, not a destination or a checklist. All

of creation is good; and our eschatology is also transformed: Micah says that

God will gather the lame and those who have been driven away.

Mahler is a “heavy”

composer of deep themes and subjects, but he has his own kind of wit if one

will hear. So does Kenny—and it is copious, and often directed at the medical

model. Referring to cayenne pepper ointments, she writes that they only made

her hunger for a vindaloo curry; or that despite x-rays and radioactive

injections, she never gained superhero powers as Marvel stories might lead one

to believe. Turning her sights to the Bible, she states that the description in

Daniel 7.9 sounds like “a wheelchair to me, and one that gives new meaning to

burning rubber.” Ezekiel 1.15-21 describes God with a massive mobility device

that is lifted by four angels with fused legs and colossal wheels that encase

wheels that glisten like topaz. If God uses a fiery, shimmering, turquoise

wheelchair why shouldn’t we?

Ableism, with its

cultural roots, is often selective. In one example, she asks if people with

eyeglasses have been targeted for prayers of cure. John Calvin even attributed

their design to science and learning as a gift of God that correct natural changes, while

leaving other devices (such as mobility aids) to the realm of differences resulting

from the corruption of sin. (Selective ableism note: of course, he needed

glasses for himself. There’s an interesting YouTube video exploring this idea). Why can’t these other adaptive devices become

mainstream, and even display a little fashion? But then, as Kenny writes, it is

human-made stuff that is orderly (especially for lawyers-turned-theologians),

while God’s canvas of creation is wild, unruly, and exquisitely messy.

In the end, Mahler finds

a sort of peace. It is somewhat defiant, especially near the end, as he directs

the horn players to stand and point their bells outward. He later went on to

write several more symphonies, each of which explores an aspect of

transformation, of finding peace, of living with meaning in an exquisitely

messy world. I look forward in hope that Kenny will also grace us with more of

her thoughts and findings as well.

Disclaimer: I borrowed this book from the Indianapolis Public Library, once again to the consternation of someone, I'm sure. The only stipulation was to return it within three weeks, which I did.