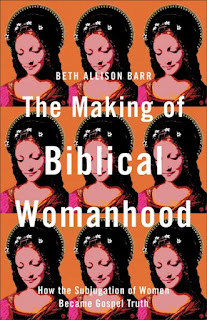

A review and disability-oriented response to Beth Allison Barr, The Making of Biblical Womanhood:

How the Subjugation of Women Became Gospel Truth. Grand Rapids: Brazos Press,

2021.

At the start of a

graduate school class titled “The History of Christian Doctrine,” the professor

apologized for the title, saying that “doctrine” probably sounded dull. The

class wasn’t, thanks to his guidance, but it’s a reminder that whether we like

it, whether we find it exciting or dull, history is there, whether we like it or not,

especially when it’s full of surprises that we’d prefer to forget. And as this book’s historical survey of a

theological topic progresses, we find out that there is much that’s been

forgotten, thereby tilting the view that many have of this history.

As I would tell my

history class, let’s begin at the beginning: the origins of patriarchy. Barr starts

with the story of a church that refused to hire a man as church secretary. He

was in need of employment and had the desired skills. The reasoning had nothing

to do with ability and everything to do with the idea that a man was above such

work.

Behind this “reasoning”

is a cultural history: as agriculture emerged, so did structured communities,

along with designations of rank and status, marking some people as more

worthy—whether of authority, certain kinds of work, or other elements of social

identity. As cultures develop, such notions often are conflated with religious

belief, and over time, become a hermeneutical standard, a move over time that is generally with the loss

of their origins. Generations of students, including myself, have written about

the imago Dei and social structure and now Barr joins us, noting that patriarchy was a result of

human sin. It exists, but is not God’s desire.

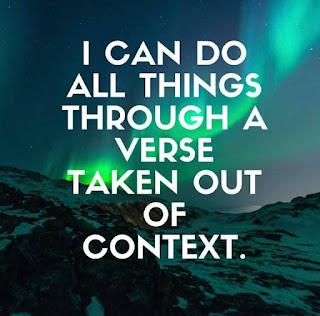

A careful reading will

reveal that many biblical passages and stories undermine, rather than support,

patriarchy. The Torah has many provisions for an inclusive society, one that

doesn’t promote rank and status. And then there’s Paul—a survey of history

shows that in the early and medieval church, his writings were hardly ever

used to support the status quo. Paul was writing to teach early Christians to live

counter-culturally in their Roman world, and how to resist the patriarchy of

the day. (With serendipity in “full” mode, the Alban newsletter of July 18,2022 notes, “In Scripture, we can see the

connection between behavior and culture when we reflect on the Apostle Paul’s

comments . . . . a transformative vision for a Christ-centered culture by advocating

for new ways of behaving within the Christian community.”)

Abetting our assumptions

about patriarchy are vagaries of translation. Few people read the preface to

translations. If one did, they would learn that King James sought to support

male, royal authority—and many recent translations refer to maintaining that

tradition. Many modern Christians thus hear in Paul a masculine authority, such

as wives should “be subject.” Paul’s original audience would have heard a

command to love as Christ did, to efface the self, and not to regard the family

as a vehicle for personal gain.

Compounding these

assumptions, we are reminded that translation is not a science and not literal.

So readers often lose track of who is speaking and who is addressed. Moreover,

the letters we have are one side of a chain of correspondence. Paul is often addressing

what was happening (i.e., “women be silent”) and reacting in disbelief

(“What!”) to offer correction. As Barr points out, Paul had reason to challenge

such accretions: “In a world that didn’t accept the word of a woman as a valid

witness, Jesus chose women as witnesses for his resurrection” (87). It should

also be noted that Paul describes himself as a mother, much as Jesus did, and

mentions women prominently among the leaders of churches.

Many translations have also wreaked havoc on gender. Inclusive readers are hardly a recent invention: in the first chapter of Genesis, a human (inclusive gender) is created, אדם ('adam). This was rendered in the Vulgate as homo/hominem (an inclusive gender term) and then as man in English. At that time, "man" was gender inclusive, but over time, it was often taken to apply to males only.

M. I should probably not venture into the hopefully unintentional

hypocrisy of those who tell us that “man” is inclusive but then act as if it’s

“male” only. An example of this is 1 Timothy 3:1–13, where the Greek uses

non-gender-specific terms, but many English translations use a series of

male-specific pronouns—none of which are in the Greek text.

Aside from the gender

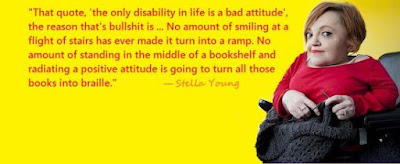

concerns raised in this book, I am (unsurprisingly) interested in the parallels

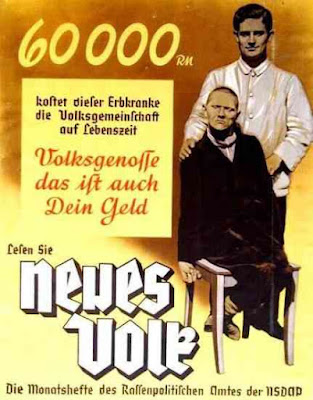

to the argument that prevailing views are accepted as cultural foundations, and

in turn used to justify theological positions. This is part of what lies behind

Theodore Hiebert’s ideas that we have

misunderstood God’s diversity due to mistranslation and cultural assumptions.

In the realm of disability, we have a Gospel example:

in John 9, Jesus converses with a blind man, treating him as a real person, and

then tells those around that their notion that disability is the result of sin

is all wrong. The extension of this story also illustrates why we need a social

model of disability: the leaders refuse to acknowledge that the man is whole,

and prefer to argue with his parents than to hear the man himself. (This does

not exhaust the material available in this direction).

In a similar approach,

Jenifer Barclay’s The Mark of Slavery

argues that the legacy of slavery created much of the modern language of

disability and influenced theological views which have survived even though

slavery has not (at least legally). As our industrial-technical age has

emphasized reading and similar technical competencies, society has singled out

conditions such as dyslexia and some neurodiversity in a way that previous ages

did not. This parallels a change of reading the λογος (logos) of John as “The Word” to be understood and

given a fixed, specific understanding, one that departs from the classical idea

of principle, grounds, reasoning, and patterns.

In the process Barclay follows, these become stigmatized as disabilities rather

than different approaches or understandings, and we lose much of the richness

of the Gospel stories.

I also remember a remark

from one person that in many ways, the oldest human disability is being female.

It’s hardly surprising, then, that this book is needed--and that there is one more

matter to address. In closing, Barr writes about the 1995 movie “The Usual

Suspects,” which, near its end, has the line “The greatest trick the devil ever

pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist.” She begs to disagree, saying

that the greatest trick was convincing Christians that oppression is godly

(172). As Matthew 23.27 reminds us, the harshest words of Jesus were to

self-appointed guardians of privilege and rank, of systems that give some

people power over others.

Disclaimer: I borrowed this book from the Indianapolis Public Library, once again pushing some generously-compensated CEO toward having to consider whether he will have to cancel a subscription to heated car seats or something similar. A nice feature of electronic borrowing for people like me is that the book is returned automatically at the end of the lending period.