A church in the Indianapolis area is conducting a summer reading group for three books. The first was Ibram Kendi, How to be an Anti-Racist. The second, which I am leading, is Amy Kenny, My Body is Not a Prayer Request. The third (late August) will be Anastasia Kidd, Fat Church.

This post shares notes and thoughts from the first group session, July 23, 2023.This places the start of the discussion during Disability Pride Month, which centers around the ADA signing on July 26, 1990.

I see a common root among the three books: liberation theology, a movement whose origins come from Latin America in the 1960’s (although, historically, one could make the case that the principles and many movements date to late antiquity). Liberation theology argues that the Bible shows a God who has a particular concern for the oppressed, who has worked through history to bring change for these groups.

When I was in seminary, our disabled students group allied with the African-American students group on the basis of liberation theology. We discussed the problems arising from judgments based on external appearances without considering the abilities of those involved. The three books in this group are linked by attitudes and activism informed by this approach. Kendi’s work shows the need for anti-racism: action and advocacy against racist attitudes and structures (it should also be noted that Kendi narrates his own growth in this area). Kenny likewise calls for anti-ableism: challenging prejudice and discrimination in attitudes, and structural changes, including but not limited to the built environment and exclusionary practices.

We discussed points of contact with disability, including:

- the vagueness and problems of rapidly evolving language, of often not knowing what to do, not having a diagnosis, having an unusual condition, or being misinformed (this can also include the difficulty of keeping up with medical advances, such as recent findings in neurodiversity)

- seeing people for who they really are, not for the disability

- not talking about it, or using euphemisms ("infantile paralysis" for polio, "differently abled") and similar fearful responses akin to early reactions to HIV

- some churches that do not believe a disability exists, which is especially true of those with neurological differences being told to behave or believe and be healed; as the book title indicates, some churches have taught a theology of miraculous healing instead of inclusion in the community

- being "out": many disabilities are invisible, and because of discrimination concerns, the people who have them are often reluctant to disclose

- general invisibility: it was only in the 1960's that people with disabilities began to appear in public social life; today's social media has been helpful in resolving this, as well as creating a sense of community and support

- impairments that are not viewed as a disability, vision correction being one example--this has a long history, including the Reformation theologian John Calvin (see section IV here) or being letf-handed (once regarded as a sign of being cursed, and still difficult in many situations)

- housing is still a problem, with refusals to accommodate and a general lack of physical access features.

We then discussed various topics that arose (and touched on others that we will likely come back to).

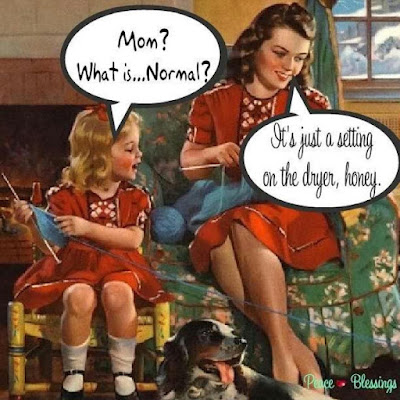

- One of the first steps is to recognize that the modern idea of "normal" is a fraud whose origins lie in statistical methods that are used to create and then justify categories and ranks. Further, “disorders” are often the result of differences in development or structures, or normal reactions to events (e.g, ASD, PTSD). See Jonathan Mooney, Normal Sucks (New York: Holt, 2019). http://flyingkittymonster.blogspot.com/2021/06/just-setting-on-dryer.html

- Universal Design is a movement emphasizing the benefits for everyone from accessible design—e.g., ramps and power doors benefit people pushing strollers or delivering packages. (https://universaldesign.ie/). This also relieves the feeling of being singled out as "that" person who has to be accommodated.

- Striving for justice needs to include accounting for opposition to the ADA from many churches, seeking equity so all can participate, and inclusion at all levels of organizations.