The second discussion session of Amy Kenny's My Body is Not a Prayer Request tied up some loose ends from before and then turned to the medical and social models of disability and their implications.

We started with some addenda to the previous discussion.

- Another factor for acknowledging justice concerns is not only opposition to the ADA from religious organizations, but later to laws such as the Affordable Care Act, particularly those dealing with pre-existing conditions, coverage of mental health, and universal coverage.

- The “crip tax” (63): costs of disability that aren’t covered by insurance. Examples include the Indiana vehicle excise tax: an adapted van can cost $60,000, and if bought as a finished unit, which is often necessary, the tax is charged on the full price, instead of an unmodified van.

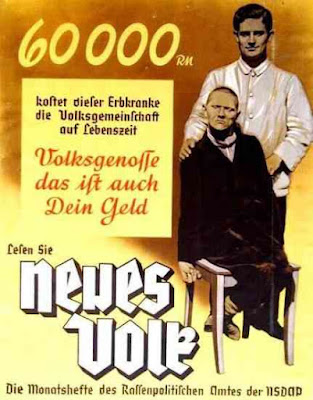

- Compounding historic opposition to the ADA and similar measures, churches have a troubled past. Eugenics was once popular among churches as well as elsewhere, and resulted in so-called ugly laws, involuntary sterilization, and unnecessary institutionalization. Thinking of Kendi's book, racial laws often specified that a small amount of Black ancestry resulted in a legal description of being racially Black despite appearances, similar to determinations of Jewish ancestry of the Nuremberg Racial Laws. People with disabilities were the first to be killed in that period as well (Aktion T4)

- ADA accommodations are enforced by civil lawsuit. They have been used as a scapegoat, e.g. Georgia voting locations that made voting difficult for minorities were "needed" because of a lack of ADA-compliant accessibility.

- Transportation is often a problem: ride-share drivers often zip by or refuse people with service dogs or assistive devices. A local residential facility doesn’t operate its transportation van on weekends, relying on ride-share, which can be uncertain.

- Restaurants seat people with visible disabilities in unsuitable locations, and while there’s less of it, servers often ask a companion what a disabled person desires. See the list on 52-53 for many other real-life situations.

- One can also get stuck in a loop: an agency or company can’t legally say no, but never get around to saying yes.

Kenny

mentions a medical model of disability (10ff). It is one of two that are

generally used, the other being social.

- The medical model focuses on medically diagnosed impairments as something to be fixed and made “normal.” It is an individual point, and leads to variations from “normal” being labeled as “disorders.”

- The use of “disorder” in a diagnosis is increasingly challenged. Trauma responses, for one, are not disorders: as one member stated, PTSD is “a reasonable response to an unreasonable experience” and a healthy response, which, if not expressed, can lead to serious problems. (An emerging term is “moral injury”). Likewise, neurodiverse conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder are not something that is wrong, but a different pattern of activity. (For a thoughtful article along these lines, see Justin Garson, “Seeing Depression as Having a Purpose Could Aid Healing” Pyschology Today June 19, 2023. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-biology-of-human-nature/202306/how-seeing-depression-as-purposeful-may-promote-healing)

- Stigma is often part of a diagnosis, and especially mental problems. “Mental illness” is often scapegoated in media and politics.

- Mental illness is often wrongly equated with neurological conditions.

- Reality is that those with mental illness are far more likely to be the victims of violence than perpetrators. Mental health is often difficult to get covered by health insurance, compounding the problem.

- One result of the medical model is the charitable appeal, portraying people with disabilities as the object of pity, and asking others to provide relief through patronizing appeals for donations and actions that involve doing things for disabled people. The Labor Day Telethon is perhaps best-known in American culture, and it has led to much discussion of “inspiration porn.” The term was coined by the late Stella Young, known in disability circles for saying that a good attitude can’t make stairs into ramps. Rather than celebrate accomplishments in context, it holds disabled people up as inspiring examples of “overcoming” their disability and is regarded as exploitation by many.

- As we have been reminded this summer, following the Revised Common Lectionary, Genesis states that God’s creation is good (Genesis 1.31) in all of its diversity.·

- In churches, the social model is reflected in full participation and use of “ministry with” rather than the charitable model of “ministry to.” It is not an “outreach ministry” but an “inclusion effort.”

- Concerns in churches include community integration and inclusion, leadership development (many still refuse or place serious obstacles to disabled leaders at any level).·

· The group is now taking a break. Sessions for Fat Church are scheduled after the break, and then there will be sessions covering all three books. A resource list for this book will follow soon.