A review of Peter Enns, How the Bible Actually Works (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2019)

In this book, intended for a non-specialist reader, Enns argues that the goal of reading and studying the Bible is not to hear a ready-made answer, but to gain wisdom through a journey of finding God and relating ourselves to the world. He bases this on three premises about the Bible: that it is ancient, ambiguous, and diverse, each of which he explores in some depth, and with a good bit of ironic humor.

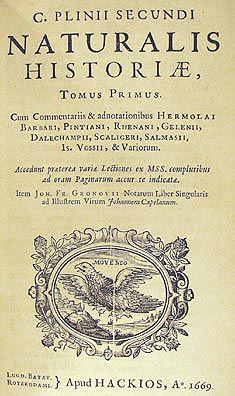

One of my favorite things about history is finding that something isn't really new, and that is the case here. In 2015, the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church of Buffalo posted a meme (above) reminding us of this point. And the culture out of which much of the Bible came also emphasized this idea of seeking wisdom:

In the tradition of Plutarch: therefore he (Apollo) proposes and sends out problems that use our reason to those who hold a philosophical nature, which creates in the soul a search for the truth, . . . because the origin of philosophy is seeking truth, and because wonder and not knowing is the beginning of seeking, it is only proper that the divine should be presented to us as an enigma (Plutarch, De E Apud Delphos 384, 385, author's translation).

As David Tracey addresses in Plurality and Ambiguity, the nature of a classic: a work whose significance endures because it addresses questions of life in a way that reaches beyond culture. Seeking to find wisdom is a quest, much like the Wesleyan pursuit of holy living.

When one uses this approach, "contradictions" become an avenue for understanding. The principles of exegesis call for us to understand the situation of a statement. An example given by Enns is Proverbs 26.4-5, which first urges the hearer not to answer fools "according to their folly" at the risk of becoming a fool, but then states we should answer them, for otherwise they will think they are wise. Judgment, hopefully made with wisdom, is a primary tool to understand and move ahead. It is a reminder of many theology classes, where a professor would state two (or more) apparently opposed positions, and ask which was right--to which the answer is "yes".

Given that this idea may meet resistance (the book is intended, again, for non-specialists, and, I suspect, this includes those who have been told and accept that the Bible is the "Word" without pondering further the meaning of λογος), Enns goes into some depth on variations of the narratives of the Bible, for example, how the book of Chronicles retells the narrative of Samuel and Kings from a much later point in Jewish history. The differences are differences of understanding how God works in our lives. And this is wisdom at work. He also explores the role of wisdom, which is personified as the divine accomplice in creation.

For disability theology, this opens a new dimension of exploration. Enns portrays a Jesus, who, as the λογος, reveals a deeper level of understanding God's work, one that goes beyond simply words on a page. Many of today's discussions of the healing stories focus on medical descriptions of the ailments portrayed. This emphasis overlooks the results, which are that the people portrayed are now included in the community and speak for themselves--it is the lack of inclusion and self-determination that are critiqued in the story, not methods of surgery.

I present two examples for thought. In Genesis 32, Jacob wrestles with God, and leaves with a new name and a disability after being touched in his hip. Disability touches all of us, and so does living a life that strives to honor God. We often hear the cliche, "we're all disabled." Yes, we are (even if we don't subscribe to the idea of original sin) but we often don't live that way. It is a similar situation to those who say "I'm not racist," but overlook complicity in a racist system.

In John 9, Jesus gives sight to a man who had been born blind. This story receives a lot of attention because of Jesus' statement that no person's sin was the cause of the man's blindness. But going further, there is a lengthy exchange among others about the man. His own statements were ignored, even when his parents stated that he was of age to answer. His eventual response was "I have told you already, and you would not listen" (NRSV). People with disabilities are familiar with this problem, and it's often summed up in the slogan "nothing about us, without us." It also reminds me of the times when servers have asked my wife what I'd like to have for dinner. It also reminds me of the assorted people in my life who have rigorously avoided asking me what I want, but either tell me what I need or ask someone else: it seems that, as someone remarked to me a while ago, the people who talk about God having a plan are so often in possession of information about what God wants everyone to do, information that God has not otherwise shared with those involved.

Practice a little wisdom. Listen to what God has for you, and listen to others.

Practice a little wisdom. Listen to what God has for you, and listen to others.