A review and reflections: Joerg Rieger, No Religion but Social Religion: Liberating Wesleyan theology. Nashville: General Board of Higher Education and Ministry, 2018.

Honored more in the breach, this popular saying reminds us that a first step in approaching theology is to remove one’s own “blinders” so that we may see the “structures of sin” that surround us. To make his point, Rieger tells a story of a presentation explaining that John Wesley’s theology is a reversal of top-down religion. At a faculty meeting, the hearers seemed unable to grasp the problem. At a meeting of disadvantaged high schoolers, the message was clearly understood, and discussion added to his store of examples.

This story came to mind when I saw a notice promoting a “freedom” rally against critical race theory (among other things) in a neighboring suburb. The notice was unravaged by the onerous demands of fact. For those who have ears and will hear (or read), this theory is an historical process that suggests we look at formative principles, examine foundations, and learn how they have affected later developments so that we can set out ways in which lasting change may be created, much as Isabel Wilkerson does in Caste.

From such analysis, we find links that couple the foundations of the social model of disability and critical race theory. One of Rieger’s principles in this book is often mentioned in discussing disability theology—the unity of the body of Christ, and, in particular, the need of each part for the others, derived from 1 Corinthians 12:21 and Ephesians 4 (the RCL Epistle reading for the 18th week in Ordinary Time, which in 2021 falls on August 1). The way we live, and how we deal with disadvantaged people, does matter.

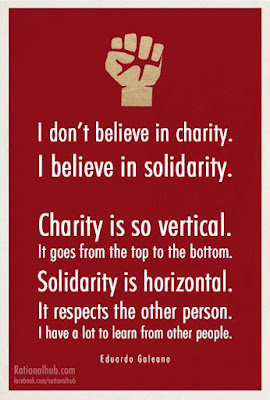

This also reminds us that, God is not at the top of an hierarchy, as most theology would have us think. Theology is the work of the people, asking where God is in our world—this is the meaning of kenosis (Philippians 2.7). Wesley set us an example, ministering to the lowest in the society of his day. It was not a patriarchal act of charity, but one of solidarity and refutation of power structures.

The ultimate expression of solidarity is inclusion. One form of inclusion, following Wesley’s footsteps, is ministry with, not to. It is not bombarding those thought to be outsiders with weaponized “truth,” but hearing the call of the disadvantaged and realizing that we are all one. As Rieger writes, “deep solidarity does not imply that we forget about our differences; the opposite is the case: deep solidarity enables us to find ways to make use of our differences for the common good” (78).

Disclaimer: I borrowed this book from the Indianapolis Public Library and thereby agreed to return it in three weeks, which I did. Joerg Rieger was my German examiner at the Graduate School in Religious Studies, Southern Methodist University, and impressed me by being perceptive enough to have me read about Wesley's social thought through German theologians. Maybe that's why I passed on the first try.