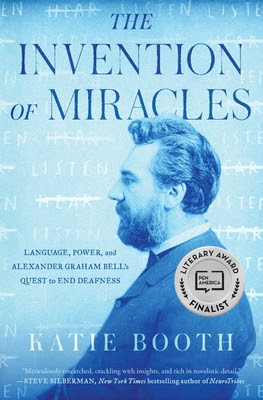

The New Miracles: a response to Katie Booth, The Invention of Miracles: Language, Power, and Alexander Graham Bell’s Quest to End Deafness (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021)

Classical tragedies revolve around a plot line of a character who acts out of a perceived noble intent. However, the character overlooks a flaw in that intent, and that flaw ultimately brings the character down. There’s a way in which this is true of Alexander (Alec) Bell, the inventor of the telephone. Bell sought to make communication easier—but in the process, overlooked that he sought to quash a culture. His efforts to promote oralism and bring an end to the use of sign language, and his promotion of early eugenics, have left a legacy that Deaf people still contend with, even though the end result has been to open new channels of communication.

Booth explores this complex legacy as she opens the book with a story about her Deaf grandmother being in a hospital. Whenever grandmother sought to sign with someone, “she was treated as a bother,” and the staff would only respond to Booth or her mother’s spoken requests (3). Some discussion of law corrected parts of that problem, but it led to reflection on her grade school history classes, where she learned that Bell invented the telephone. This seemed “as absurd as introducing Adolf Hitler as a vegetarian who once ruled over Germany” (12).

Pursuing a more complete story, Bell’s work began with his father, who sought to devise a universal alphabet for missionaries. Using this, they could read the Bible aloud in any language, even they didn’t understand it. (We’ll save the theological discussion of this notion for another post). Believing that speech was what made one human, it followed that any sentient being needed to learn to speak—with a voice, not with signs. Despite abundant examples, which included his own mother, Bell stuck with that notion, which led to the idea that being Deaf was a burden, a marker of an unacceptable difference, and something to be eliminated through training and marriage restrictions.

Bell lived in a time of change: industrialization was creating systems emphasizing and transforming “normal” from mathematics to identity and proclaimed them as the path to a new age through eugenics. “Freak” became the umbrella term for racial, ethnic, developmental, gender, and physical differences. The tragic flaw enters: there is little indication that Bell was insensitive to suffering and inequality. Booth recounts several instances where he was distressed by racial discrimination. But, in a move that we all might be forced to confess, he did not recognize his own involvement in “a larger struggle between normalcy and difference, between saving and being saved, between empowerment and charity” (77), thus setting the stage for the tragic character’s downfall.

John Wesley was an admirer of the classics and early church fathers who struggled with these concerns. Today’s “nothing about us, without us” was not yet a motto, but concerns that those on the margins should be heard are clear from his writings. He famously “consented to be more vile” – to change his ways in seeking inclusion. Sadly, Bell followed the thinking of many in his time who saw defects as something to be eliminated rather than embrace more social models and accommodation. Today the struggle continues: do people who are different have “special needs” or functional requirements? Are they included in leadership, or are they a target group (ministry with or ministry to)? Is a difference a weakness to be hidden? As the author notes, does empowerment come through assimilation or recognizing and honoring diversity? We still struggle, which is why the classics are still with us. The new miracle, as Teilhard de Chardin wrote, will come when we harness the energy of love, the love that was central to Wesley.

Normal abnormal disclaimer: much to the chagrin of various greedy corporations, I borrowed this book from the Indianapolis Public Library, and even though they no longer charge late fines, I did return it on time.