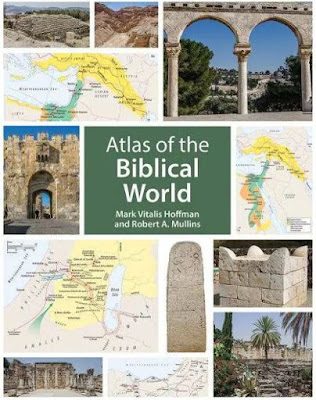

Mark V. Hoffman and

Robert A. Mullins, Atlas of the Biblical World. Minneapolis:

Fortress Press, 2019.

It

was in second grade, I think, that everyone in my class received a

state map. We didn’t do much with it, but it was a fold-up wonder

that opened a new world. Looking at it, I saw where we lived, places

nearby that we sometimes traveled to, and places further off that

sounded fascinating. Thus began an interest that developed as I

pursued historical studies—learning how geography has had an

integral role in shaping events, and growing in understanding how

others live.

As

I moved into a major of religious history, it seems natural to say

that Bible atlases were along for the journey. More so than for many

other books, one is needed here—its events take place in a

generally unfamiliar land, there are often varying accounts of an

event, as well as different names than other sources use, and other

problems that challenge a reader. Bible publishers have responded

with maps bound in with the text, but they are often dated and

require flipping pages, so a stand-alone version that can sit next to

one is a useful resource. Mine received a lot of use; I suspect I’m

not alone in wearing out copies of the Oxford Bible Atlas just

in time to buy a new edition.

While

the Oxford atlas remains a good choice, this recent offering from

Fortress provides worthy competition. In general, each page has a

section outlining the text references, books or chapters and

background on one leaf. Opposite that is a map illustrating the

geography and movements involved. There are five sections that flow

chronologically: Beginnings, The People of Israel in Canaan, A People

Divided, Invasion and Occupation, and Jesus and the Emergence of

Christianity.

I

mention this organization to remember one of my seminary professors

who remarked of one paper that simply being aware that the book of

Jeremiah is not in chronological order is useful. The Hebrew Bible is

organized by themes – Torah, Prophets, and Writings. While the role

and places of the prophets are often missing here (which I see as the

book’s greatest lack), the whole does a good job of helping make

the storyline of the Hebrew Bible clear.

The

Christian scriptures start with five books that are only vaguely in

chronological order (like the Hebrew records, a trait that often

frustrates modern western readers), and often alludes to events that

are obscure. It then pries into someone else’s mail, often

conjoining the letters and obscuring the background of events. Here

the layout and background are again useful.

Overall this approach is helpful as the authors relate the biblical stories to

other historical events, thus removing some of the “bubble.” It’s

easy to forget about the wider world, one that is only tangentially

mentioned most of the time. Another helpful feature is reference to

archaeological findings and what they tell us about the story.

Archaeology doesn’t “prove” the Bible, but it does tell us a

lot about the background of the stories, and thus help us understand

it. The section “Invasion and Occupation,” dealing mostly with

the inter-testamental period (when much of the Apocrypha were

composed) is particularly good in helping to understand the political

movements which led to the tensions, situations, and parties of the

Gospels.

In

summary, then, this a very

effective tool for understanding. It’s

not the most comprehensive,

but that isn’t the goal.

It’s factual, which means that some of the popular legends aren’t

included, but that’s fine with me. Mark

Twain wrote in the conclusion of his rollicking book The Innocents Abroad that “travel is fatal to

prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness.” It

also is fatal to fakery (something Twain remarks on a lot in

that book!) and expands

horizons and knowledge. You

may well find me online, looking at Google maps (especially with the

new accessibility features, but

stretching our boundaries

also includes a good book of

this sort.

No comments:

Post a Comment