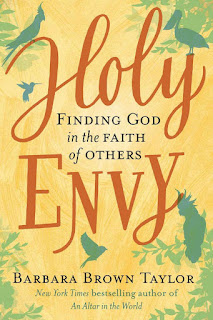

A review and some thoughts: Barbara Brown Taylor, Holy Envy: Finding God in the Faith of Others (HarperOne, 2019)

Choose as many answers as you like: If you do that or go to __, you’ll lose your faith:

• Science class

• That concert

• College, especially at a state university

• A United Methodist church

• Marry that woman

• Seminary

• Graduate school

In roughly chronological order, I have heard all of these, and have probably forgotten just as many. Somehow, just like that phrase “yet she persisted,” prevails, πιστις also persists—and may her tribe, including cousin σοφια, increase!

An education is supposed to, by origin and definition, challenge and bring new horizons (ēdūcō "I lead out/away”). And when that leading out happens in the field of religion, it can be earth-shaking. Religions often describe encounters with the divine as producing so much change that people take on new names and, in the case of Moses, a new face. The prophets of ancient Israel spoke of bringing new hearts, minds, and even a new earth as their contemporaries in India spoke of finding freedom from the burdens of acquisition. A once-obscure Jewish rabbi spoke of bringing new life. Periodic renewal movements call us back to those ideals, removing the accretions of centuries of institutionalization and its power plays.

Although I often also teach history and anthropology, there is a strong element of religion in those fields—as anyone can observe, it has historically been a source of conflict, but it has also inspired some of the world’s great art. This is one reason this book resonated with me. Student and teacher alike finish a course with life turned over.

Taylor posits three rules for talking about religion, which she derives from Krister Stendahl: ask its adherents about the religion, not its enemies; don’t compare your group's best to their worst; and leave room for holy envy (65). To this she adds a corollary, derived from Robert Farr Capon’s Hunting the Divine Fox: Images and Mystery in Christian Faith (Seabury, 1974): understand that humans are finite, and that trying to understand God is similar to an oyster in a tide pool trying to understand a prima ballerina dancing on the shore. At best, we see those puzzling reflections that St. Paul wrote about. But humans are not fond of admitting that there are limits to our abilities. Thus, as Taylor puts it, as brilliant as our tide pool theologies may be, the brilliance of the ballerina exceeds them all (77).

There are many other memorable points in this book. One is that very little of our religious talk is actually religious—but then, most Christian teaching is based on the lives of people who were strangers to religion. With so many outsiders in the story, why is “the other” so fearful? Is it because the Bible is too familiar to us, and we no longer read, see, and hear what is on the page? Being a student means learning, continually, not only what is there, but what is not known, especially when it’s about something we’ve been told or want it to say. Scripture has its own voice--sometimes more terrible than wonderful--but it has never failed to reward close attention (as I mention in a previous post).

Technical and vocational education is absolutely necessary, but they do not lead us to understanding our past and its treasures, which in turn teach us how to lead a responsible and respectful social life. The study of religion (and other liberal arts) opens us to a wider world. We don’t need to fear that learning Spanish will cause us to lose our ability with English, she writes (210). Having taught some classical languages at times, I have found that this is true—understanding another language and the culture that goes with it will deepen your own language. You won't lose your faith, you'll gain a new aspect. You may lose the old box you kept God in, but will gain a new, more complete perspective.

In the end, we need to ask, what is teaching about?--and one the other side, what is learning about? Teaching is dangerous, which is why authoritarians and dictators have, throughout history, sought to control it. Learning is the art of becoming unsettled and pursuing the truth of the divine enigma to awaken to new possibilities.

Disclaimer: I borrowed this book from the Indianapolis Public Library, and promised to return it within three weeks. I fulfilled that promise. The check-out receipt also informed me that I've saved more than $250 this year by using the library, after deducting my share of taxes. This is a far better, and more informative statement that the nonsense that Kroger puts on our receipts about how much we've saved by shopping there--for one thing, compared to what? As with too many things in life, we spend a lot of time listening to meaningless numbers and too little thinking about what matters.